The Magic of Lazy Lists

Introduction

As the Scala 3 - book points out, Scala has a rich set of collection

classes. As well as List, of course, it also has a solid implementation of LazyList. If you're not sure what that is, or what is used for, read on and find out, plus even better I will walk through a full implementation of LazyList that can do some magical things.

Scala List can represent collections of zero or more, stored as a linked list, with the details of the underlying data structure abstracted away.

In my video NonEmptyLists more or less I talked about how

you can build a variant of List that can only be a collection with one or more items.

In this video, I will present the theory and practice of building a LazyList type, that adds the additional capability of controlling when elements are evaluated.

All the code written in this post, and the accompanying video The Magic of Lazy Lists can be found in my new educational Scala library Duct. In order to produce this implementation I studied the code of the Scala standard library (both the current version and history versions which are less sophisticated but also easier to read), as well as other implementations such as that of the ScalaZ Ephemeral list. The resulting code is a combination of these with some of the best parts of both, as well as taking some advantage of Scala 3 features along the way.

Implementing Lazy Thing

LazyList is easier to understand if you have a good grasp of different evaluation models in Scala, so let's explore that with a custom class called LazyThing.

With this implementation, LazyThing is just a wrapper of values, with a get function that returns the value. This is what we call eager, or strict evaluation. When I pass

the expression {println("evaluated"); 10 is passed into the LazyThing constructor it is evaluated immediately and stored in the class. Later when the user calls the get method

we find that we just get the value; nothing is evaluated again.

class LazyThing[A](a: A): def get = a val lt = new LazyThing({println("evaluated"); 10}) // evaluated lt.get // val res4: Int = 10

When working with a LazyList we want to be able to populate it with expressions but without having them evaluated until we are ready (what Haskell refers to

as call by need). What else can we use in Scala that only evaluates when we want it to? Functions! If the argument was a function, we could simply

call it when the user calls get, making it lazy.

Now when we create the class nothing is evaluated until we call get, and then it is evaluated every time. This evaluation mode is called always.

class LazyThing[A](a: () => A): def get = a() val lt = new LazyThing(() => {println("evaluated"); 10}) // scala> lt.get // evaluated // val res15: Int = 10 // scala> lt.get // evaluated // val res16: Int = 10

The LazyList structure is not about always evaluation though, it is about lazy or call by need evaluation. We want to be able to remember the result

of evaluated list elements, and never evaluate them again. This memoization is the next step.

class LazyThing[A](a: () => A): var evaluated = false var value: A = _ def get = if evaluated then value else evaluated = true value = a() val lt = new LazyThing(() => {println("evaluated"); 10}) // scala> lt.get // evaluated // val res17: Any = () // scala> lt.get // val res18: Any = 10

Now you can see that the value is evaluated only once and we can retrieve it multiple times. Memoization is good because it saves us from recomputing

values, but it also means we must be mindful of memory use and hanging on to references to the internal structure of our LazyList so as not

to consume memory that is no longer needed.

Two final simplifications using Scala features make this much more succinct. The mechanism of passing an argument as a function executed only on first reference is implemented within Scala and known as call by name. Rewriting like below uses that mechanism instead.

Secondly, we can replace the manual memoization code that remembers the evaluated value with lazy val which does the same thing but, again, is built into the compiler.

class LazyThing[A](a: => A): lazy val get = a val lt = new LazyThing({println("evaluated"); 10}) // scala> lt.get // evaluated // val res24: Int = 10 // scala> lt.get // val res25: Int = 10

Beginning LazyList

Let's begin by representing the LazyList as a sealed trait, which will be the object through which users interact with the collection.

sealed trait OurLazyList[+A]: def head: A def tail: OurLazyList[A] def isEmpty: Boolean

Of note here is the +A variance notation. It's important to know about and understand variance when making libraries in Scala, slightly less

important when writing application code. A short explanation of variance is that it is short for "variance under inheritance".

Let's say we have a type Loan and two other subtypes of Loan, Credit Card and Amortized Loan. If you have some function that takes Loan

and prints the outstanding balance, you would expect through normal rules of inheritance to be able to pass in a Credit card or an amortized

loan in place of the Loan. You can use a subtype of loan wherever the compiler is expecting a loan. That is what is known as behavioural

subtyping.

What variance under inheritance refers to, is what inheritance means when we have some parameterized type such as a collection. If I have a function that takes a list of Loans, should it accept a list of subtypes? Credit cards for example. Because the answer to this is, no not always, Scala includes variance annotations so that you can choose the variance relationship you want as needed. I'll come back to this topic in more detail in a later video.

LazyList will have a companion object containing all the static methods that will be used to create and manipulate lazy lists. The first thing

we need is a representation of empty list. We add that to a new companion object.

object LazyList: val empty = new LazyList[Nothing]: def head = throw new NoSuchElementException("Cannot get head of empty lazy list") def tail = throw new UnsupportedOperationException("No tail of empty lazy list") val isEmpty = true

Lazy list has the type Nothing. Nothing is at the bottom of Scala's type hierarchy meaning it is the subtype of everything. Now it's not a useful type

in itself, because you can't do anything with it, but it is really useful in this context… our empty list is a singleton value shared by all lazy

lists, we only need one. Why does this work? Because of the variance annotation above. We said that a list of subtypes of A would be acceptable as

list of A.

So now we are able to create lazy lists with nothing in them using LazyList.empty. The next step is to be able to create lists with elements inside. We will call this the cons method,

as it will be used to construct lists one lazy element at a time.

// object LazyList continued: def cons[A](hd: => A, tl: => LazyList[A]) = new LazyList[A]: lazy val head = hd lazy val tail = tl val isEmpty = false

With this small amount of code we have a functional (no pun intended) lazy list.

val ll = LazyList.cons({println("evaluated!");10}, LazyList.empty) // nothing is printed yet! ll.head // evaluated! // val res9: Int = 10 ll.head // val res10: Int = 10

Here you can see that constructing the list did not evaluate the value we passed in to be the head of the collection. Once we retrieved the head we got the evaluation happen, but subsequently we did not not. Nice.

Pattern matching and the "cons operator"

In Scala you can construct lists using the so-called cons operator ::. For example:

val l = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: List.empty // Creates a List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

This is convenient so Scala's standard LazyList also implements this using the syntax #::. Let's do the same for Duct. There are two things to note here:

- To make this work we want #:: to be a right associative function that

cons's a new head for the list to the tail which is to the right - The type of the operation should be a cons operation on a list.

To append 1 to the list val ll = (2,3) we need to write 1 #:: ll and we want the compiler to evaluate this as:

ll.#::(1) // where the type of LL is LazyList[Int]

Note that in Scala, by convention, anything ending in a colon is right associative, which is what we want here. Also not that in Scala 3 we can write this as an extension method. In the standard library you'll see code like the following:

implicit def toDeferrer[A](l: => LazyList[A]): Deferrer[A] = new Deferrer[A](() => l) final class Deferrer[A] private[LazyList] (private val l: () => LazyList[A]) extends AnyVal { /** Construct a LazyList consisting of a given first element followed by elements * from another LazyList. */ def #:: [B >: A](elem: => B): LazyList[B] = newLL(sCons(elem, newLL(l().state))) /** Construct a LazyList consisting of the concatenation of the given LazyList and * another LazyList. */ def #:::[B >: A](prefix: LazyList[B]): LazyList[B] = prefix lazyAppendedAll l() }

scala.collection.immutable.LazyList.scala

With Scala 3 we can simply implement this as an extension method on the LazyList trait. Much nicer.

extension [A](hd: => A) def #::(tl: => LazyList[A]): LazyList[A] = LazyList.cons(hd, tl)

Now we can create lazy lists more easily as follows:

val ll = 1 #:: 2 #:: LazyList.empty // val ll: LazyList[Int] = LazyList$$anon$2@687292c5

Creating a lazy list with the cons operators is one thing but users will expect to be able to deconstruct lists in a pattern match expression to. Let's add that functionality next.

In Scala you implement pattern matching on a particular type by implementing unapply on an object with that types name, in our case #::.

object #:: { def unapply[A](s: LazyList[A]): Option[(A, LazyList[A])] = if !s.isEmpty then Some((s.head, s.tail)) else None }

The way unapply works is the opposite of a constructor. Given a constructed type, unapply tries to extract the pieces. This is a partial function, it does not have to succeed, so it returns the pieces as an Option.

Now we can write lazy code using pattern matching:

def ourMap[A, B](ll: LazyList[A], f: A => B): LazyList[B] = ll match { case hd #:: tl => LazyList.cons(f(hd), ourMap(tl, f)) case _ => LazyList.empty }

Iterating over Lazy List

Note that although the destructuring (pattern matching) of lazy lists is often useful, in my final implementation for the Duct library I opted for the following more simple approach to the map function, shared here because I implemented many of the functions that iterate over lazy lists in the following way:

def map[B](f: A => B): LazyList[B] = if isEmpty then LazyList.empty else LazyList.cons(f(head), tail.map(f))

Another useful function is forEach, which you can use to execute some action across the lazy list. This function highlights a couple of interesting things.

- When working with laziness always consider when you want preserve it versus lose it. The forEach function by definition must visit every element of the list and therefore does not preserve laziness.

- If possible you should make recursive functions tail recursive, otherwise they are limited by the stack. This implementation is tail recursive. We can tell the compiler to make sure that it is with the annoation.

@tailrec final def forEach(f: A => Unit): Unit = if !isEmpty then f(head) tail.forEach(f)

And you can use it as follows. Note that I'm using the LazyList.apply method here is a convenience to create a lazy list from a variable argument list.

val list1: LazyList[Int] = LazyList(1,2,3) println("forEach list1") list1.forEach { a => println(a) } // forEach list1 // 1 // 2 // 3

Filtering

Another part of the implementation worth looking at is dropping elements that pass or fail some filter, namely filter and dropWhile. Let's first think about what the semantics are here in terms of laziness.

- Given a lazy list and a filter function we want the user to be able to iterate through them

by need. - When the user calls head on a lazy list where many elements fail the filter before a good one comes, many elements are evaluated.

- We must stop evaluating the elements as soon as we find one that passes the filter, and return that as a lazy list to the caller.

We have to be careful about laziness then. Let's first think about dropWhile. This takes lazy list with all the failing elements dropped.

@tailrec final def dropWhile(f: A => Boolean): LazyList[A] = if isEmpty then LazyList.empty else if f(head) then tail.dropWhile(f) else this

Now since we want this to work on many elements potentially, it is important to be tail recursive. With dropWhile we can take list such as LazyList(1,2,3,4,5) and drop all elements less than 3. What we get back is LazyList beginning with 3.

Take a moment to think about which elements have been evaluated at this point.

Whether you reason about it by looking at the code or thinking about it semantically, the answer is that the 3 is evaluated and the 4,5 elements are in a lazy tail. dropWhile then will evaluate elements up to and including the first one that should not be dropped.

Once you implement dropWhile it can be used to implement filter with the requirements we came up with above.

def filter(f: A => Boolean): LazyList[A] = val dropped = this.dropWhile(a => !f(a)) if dropped.isEmpty then LazyList.empty else LazyList.cons(dropped.head, dropped.tail.filter(f))

Infinite lists

Quite a few years ago I was working through a Haskell tutorial for beginners. Some of the examples worked with infinite lists; mapping them, filtering them, and zipping them together. At the time my knowledge of evaluation and laziness was not sophisticated. As they say, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Since Haskell was doing things more advanced than I understood at the time, I thought of infinite lists as being a magic trick.

As you've seen so far, I hope, the mechanisms of lazy evaluation make working with infinite lists possible and don't require a lot of work. Let's look at how what we've done so far scales effortlessly from small lists to infinite ones.

def repeat[A](a: A): LazyList[A] = a #:: repeat(a) def from(n: Int) : LazyList[Int] = n #:: from(n+1) def iterate[A](a: A)(next: A => A): LazyList[A] = a #:: iterate(next(a))(next)

Note how these functions build on what we did so far, and give us ways to declaratively create infinite lists.

repeat provides a lazy list with a head of type A. When the use takes the tail they get the same thing and so on forever. This gives us a definition of an infinitely repeating constant.

from shows how we can incrementally generate numbers from some starting value n. Note that the tail is a function that takes input from the previous call; in this way we can pass information through an infinite chain of computation!

iterate is a generalisation of this allowing you to take some function that creates a new A from the previous one, forever.

Of course, we don't want to actually evaluate infinite lists because we don't have time for that, so you would use take and drop and other filtering mechanisms to work with only the values you are interested in. As we will see, there are times when you don't know how many of a thing you need and it may be expensive to generate them, so call by need evaluation is what we want.

Fusion of operations

Imagine the following code.

val lotsOfThings = List.fill(1)(10000000) lotsOfThings.map(a => expensiveCalculation(a)).filter(a => a < 10).map(a => expensiveCalculation2(a)).take(10).sum

With a strictly evaluated list what happens here?

mapwill iterate over the large list, doing expensiveCalculation 10m times and making a new list of 10m elements.filterwill walk that new list and create a new list with up to 10m elements that pass the filter.mapwill take those elements and create a new list after calling expensiveCalculation2 on each elementtakewill drop all elements after the 10th onesumiterates over the elements

Whilst this kind of code is not typical, you are hopefully not working with lists this big, but if the use case requires it, then lazy lists provide a potentially much more efficient way of working.

The same code as a lazy list would work this way.

maptakes the large list and returns a lazy list where, when evaluated, head will have expensiveCalculation applied to it. This is O(1).filterwill internally calldropWhile. Let's pretend the filter is true because a < 10 and we return a new lazy list with the filter but paused at the first element.mapwill take that list and again, return a new lazy list that is unevaluated and ready to run expensiveCalculation2 if anyone asks.

Observation… we are turning our list of values into a list of delayed computations. This takes up more memory than a list of values because each step is wrapped in a Function object.

takewill now return a lazy list that keeps track of a counter and stops (returns an empty tail) when it runs out, so we set a bound on our computation.sumokay now we're going to do a bit more work. sum callsfoldLeft(see below), which by definition must evaluate all the items and combine them to a single result

@tailrec final def foldLeft[B](z: B)(f: (B, A) => B): B = if isEmpty then z else tail.foldLeft(f(z, head))(f)

- Now more serious evaluation will happen. What we have at this point is a sort of stack of computations for each successive element. We will call expensiveCalculation1 and expensiveCalculation2

only as often as neededto evaluate the 10 elements.

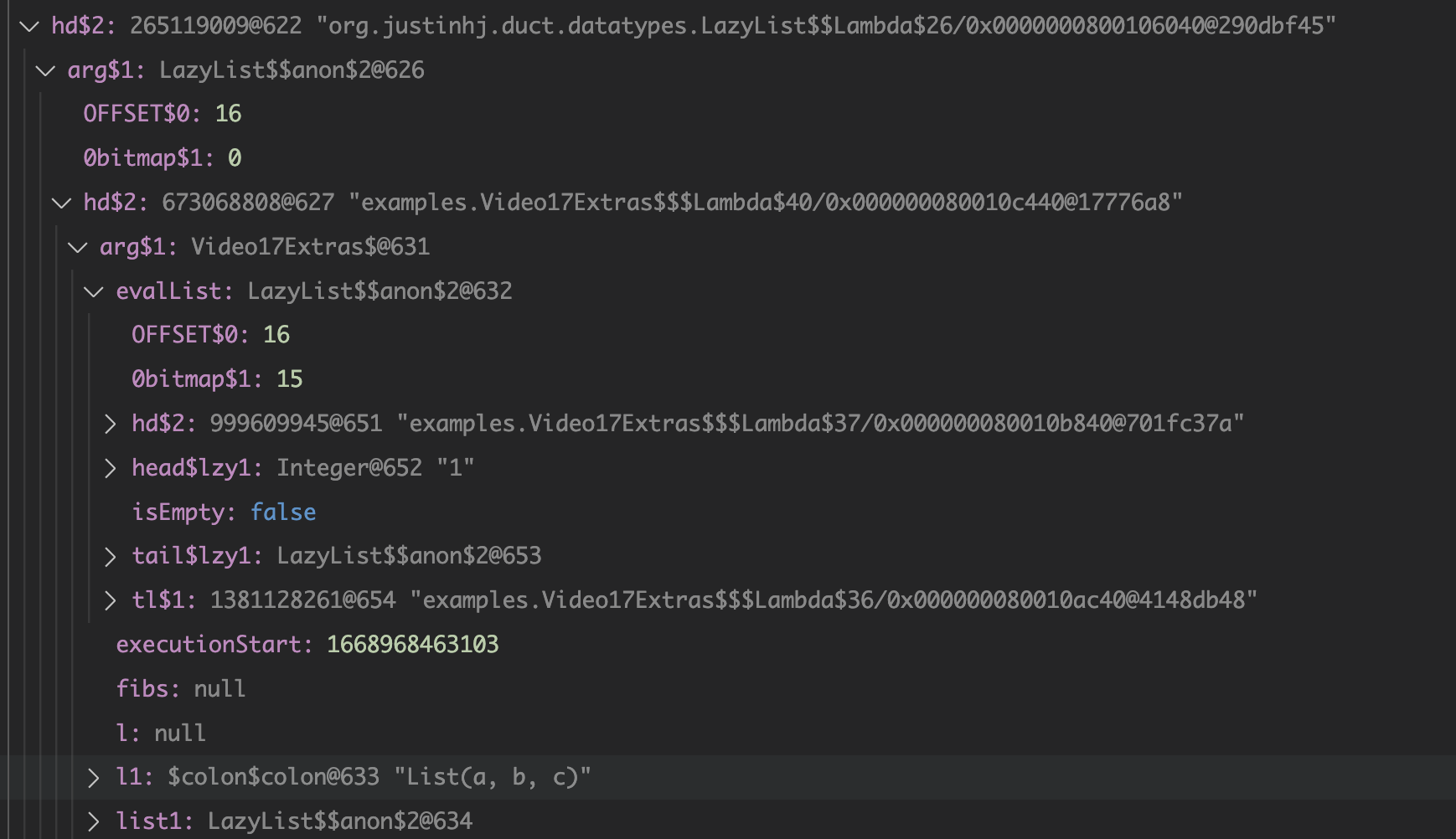

This is all rather hard to conceptualize, so here's a picture that may help. The call stack shown in the middle of the foldLeft shows that the lazy list we evaluate consists of a stack of function calls that are waiting to happen.

Fusion of operations means that a sequence of complex, expensive operations, can be limited to only the number of elements you are interested in and performed per element, not across the whole collection. This is the essence of being able to control evaluation for your own needs.

This gives us some insight on when to use a lazy list (or equivalent structures such as streams, iterators), rather than concrete immutable containers.

Use lazy lists when you need to execute an expensive sequence of operations and you don't expect to consume the majority of the collection.

You need to use some discretion here. If you can't guarantee that the whole list won't be executed, it's probably not a good use case. But this technique translates well to a computation where we never see the whole list (streaming applications that work with Kafka and Kinesis for example).

Laziness for convenience

Some algorithms require you to provide a list of things but you don't know how many things you need in advance. Here's an example that appears in the paper Applicative Programming with Effects that transposes a matrix.

You can see this code also in my post about the paper at What's Ap?, although the coverage there is more about how this operation can be written in "the applicative style".

First, let's represent a 2-dimensional matrix as a lazy list of lazy lists.

val matrix = LazyList( LazyList(11, 12, 13, 14, 15), LazyList(21, 22, 23, 24, 25), LazyList(31, 32, 33, 34, 35) )

The idea of transposing a matrix is you "rotate" it such that if you started with n rows and m columns, you would end up with a rotated matrix with m rows and n columns.

Rotated by hand and represented in code, this 3 by 5 matrix should be transposed to the following.

val matrix = LazyList( LazyList(11, 21, 31), LazyList(12, 22, 32), LazyList(13, 23, 33), LazyList(14, 24, 34), LazyList(15, 25, 35) )

In order to implement this a nicely functional, declarative way, we first need a helper function zipWith that takes two empty lists and lets us combine them with a function.

def zipWith[A, B, C](as: LazyList[A], bs: LazyList[B]) (f: (A, B) => C): LazyList[C] = as.zip(bs).map { case (a, b) => f(a, b) }

An important property of zip is that given two lists it combines them together into a new list of tuples, the length of which is bounded by the shortest one. This means we can combine zip and lazy lists to zip together two lists, one of which is infinite and the other is bounded. That's the technique used here.

def transpose[A]( matrix: LazyList[LazyList[A]]): LazyList[LazyList[A]] = if matrix.isEmpty then LazyList.repeat(LazyList.empty) then else zipWith(matrix.head, transpose(matrix.tail))(_ #:: _)

Is it easy to understand? No, it takes a bit of thinking about to understand what is going on (as an exercise I'd suggest adding some println to see how it works). What's more

interesting though, is that this is a much more functional, declarative version of matrix transpose. Imagine writing this in Go and you will do it as a for loop, taking care not to

make any mistakes. Even though matrix transpose is simple, functional programming scales up to bigger more complex programs, whereas the imperative version is more

of a one-off implementation.

The "trick" in the code above is in the LazyList.repeat. The iteration of the transpose works along each row of the matrix producing the new columns with cons, but at some point it runs out of rows and it needs another row of empty lists to finish the new rows off. How many empty lists does it need? Well, we could work it out by counting, but why not just say

here is an infinite number, and let the zip figure out when to stop?

Folding left and right

There are a couple of interesting things to say about folding lazy lists. Firstly let's look at stack safety.

As we saw earlier the amount of memory used by a lazy list can be higher than with a regular list since with fusion between operations we can end up with a stack of function objects before it is evaluated. For that reason and just in general we may want to operate on large lists, it's important to consider which operations are stack safe and which are not.

For a stack safe function I present foldLeft.

@tailrec final def foldLeft[B](z: B)(f: (B, A) => B): B = if isEmpty then z else tail.foldLeft(f(z, head))(f)

This is a so-called aggregate function that takes a collection, in this case, iterates over it and produces some aggregate value. The supplied function

from the user is applied to each element along with some accumulating value. In the case of this implementation, the foldLeft recursive call is in tail position

which means we can assume it uses tail call optimization. We add the annotation to tell the compiler we think so, and it will both complain if it is not eligible.

def incN(n: Int, inc: Int): LazyList[Int] = LazyList.cons(n, incN(n + inc, inc)) println( incN(1, 1).take(10000000).foldLeft(BigInt(0)) { case (acc, a) => acc + a } )

This function adds up 10m integers and as such takes up a lot of stack space and crashes. Except it doesn't! Why? Because of the tail call optimization.

Now it will, in fact, take a good few seconds on modern hardware, which is a long time, and it may in fact crash with out of memory or be pathologically slow. Why? Because we are creating a lot of garbage here, in the order of gigabytes, and that takes a lot of work to clear up.

Make sure you have a decent amount of heap and use the G1 garbage collector via these settings (this is for running sbt, you can set the same JAVAOPTS for IDE's and so on).

SBT_OPTS="-XX:+UseG1GC -Xmx4G" sbt

So foldLeft is stack safe, how about foldRight?

def foldRight[B](z: => B)(f: (A, => B) => B): B = if isEmpty then z else f(head, tail.foldRight(z)(f))

Note that the problem here is that the recursive call is not a tail

call position, in this case, the user function f is. That means we

can't use the tailrec annotation and it will not be tail call

optimized.

Can we infer from this situation that foldRight is useless? No actually. It has a property that foldLeft does not, that of being able to terminate early. Just like with fusion of operations,

the early termination of foldRight can be used to save us work, and make code more efficient.

How does that work? The "trick" here is that the second argument of the user function, the accumulator, is a call by-name value. It's lazy! That means we don't have to evaluate it.

This example code uses foldRight to find "tuna" in a list of fish.

def hasTuna(ll: LazyList[String]): Boolean = ll.foldRight(false){ (next, z) => println(next) if next == "tuna" then true else z } hasTuna(LazyList("salmon", "shark", "tuna", "moray", "goldfish", "eel")) // prints: // salmon // shark // tuna

This is simply not possible with foldLeft, nor is it possible if you don't use a call by-name argument for the accumulator in foldRight. If you're not sure why it is not possible for foldLeft, try putting some println statements into things that you foldLeft and foldRight and see the order in which things are done.

By the way, if you try this with the standard library you'll find it does not work the same way. The signature of foldRight is as follows:

def foldRight[B](z: B)(op: (A, B) => B): B

Without even trying it we know that it must expand the whole collection, although feel free to try it if you need to prove it to yourself. There has been some discussion on this, for example.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/7830471/foldright-on-infinite-lazy-structure http://voidmainargs.blogspot.com/2011/08/folding-stream-with-scala.html

As noted in the second example the following code will work with a lazy aware foldRight only.

LazyList.repeat(true).foldRight(false){_ || _}

Last words

Maybe LazyList is not something you will use very often but I think some of the ideas here are central to functional programming. When you are working with streaming libraries like fs2, or effect libraries like Zio, this idea of building up some structure first, then evaluating it, is very powerful, and understanding lazy lists in some depth will hopefully help your way of thinking in your day to day Scala code!

Thanks for reading, if you enjoyed this content please share with a friend. If not, drop me a note and tell me what I can do better next time.

References

Functional Programming in Scala (aka the red book) - has a great chapter on lazy lists Functional Programming in Scala - Manning Press

LazyList Scala standard library 2.13 - modern day production ready code https://www.scala-lang.org/api/2.13.x/scala/collection/immutable/LazyList.html

Stream from Scala standard library 2.7 - older and simpler version which I found easier to understand https://github.com/scala/scala/blob/v2.7.7/src/library/scala/Stream.scala

Scalaz Ephemeral Stream - did some things I liked too https://github.com/scalaz/scalaz/blob/ea81ca782a634d4cd93c56529c082567a207c9f6/core/src/main/scala/scalaz/EphemeralStream.scala

All of the code for the Lazy List class can be found in the Duct library here https://github.com/justinhj/duct/blob/video17/core/src/main/scala/org/justinhj/duct/datatypes/LazyList.scala If you dig around in the code, or find in files for LazyList, you will see there is also a test suite and a few examples.