Monad Transformers - the prelude to ZPure

Readers and Writers and Transformers

BTW you can check out the video here instead: Functional Justin - Another Angle on Monad Transformers

There are twenty pages here or over an hour of videos, so let me help you decide if it's worth your time.

Who are you?

You are a Scala programmer or interested in Scala and may have some Haskell or interest in pure functional programming.

What do I cover?

- Introduction to Monad transformers

- Implement the WriterT monad in Scala 3 from scratch and used in a program

- Implement the ReaderT monad in Scala 3, also from scratch, and use it

- Why not both? Stack the Reader and Writer monads on top of each other

- Effect rotation and ZIO Prelude's ZPure, another approach to combining effects

Evaluating expressions

In previous blogs and videos, I've described a program that evaluates arithmetic expressions as this is a nice testbed for various functional effects. So far I've demonstrated how by using different data types and type classes one can make the same program behave differently.

This is important for a couple of reasons. It means that you can compose interesting programs from smaller, well-understood components, and because we can understand and change the behaviour of our program by using different types.

As a starting point, lets begin with a version of the program that has error handling using the Either data type and Numeric which is a generic implementation of numbers.

If you didn't catch up on earlier posts let's recap. An example run of the program requires an environment (symbol table) provided using the Scala 3 implicit mechanism (using the given keyword). I call eval on a sample expression tree which yields either a Right or a Left result since I'm using Either as the result effect type.

given envMap: Env[Int] = Map("x" -> 7, "y" -> 6, "z" -> 22) val exp1 : Exp[Int] = Mul(Var("z"), Add(Val(10), Sub(Var("x"), Var("y")))) val eval1 = eval(exp1) println(s"Eval exp gives $eval1") // [info] running Scala3EvalEither // Eval exp gives Right(242)

I represent the errors as a Scala 3 enum which is a nice way to create ADT's (algebraic data types), similar to how you would do it in Rust.

enum EvalError { case InvalidSymboName case SymbolNotFound case DivisionByZero }

The next things to look at are an ADT to represent the program steps a return type.

enum Exp[A]: case Val(value: A) extends Exp[A] case Add(left: Exp[A], right: Exp[A]) extends Exp[A] case Sub(left: Exp[A], right: Exp[A]) extends Exp[A] case Mul(left: Exp[A], right: Exp[A]) extends Exp[A] case Div(left: Exp[A], right: Exp[A]) extends Exp[A] case Var(identifier: String) extends Exp[A] type Env[A] = Map[String, A] import Exp._ type WithEnv[A] = Env[A] ?=> Either[EvalError, A]

The Env type is a simple map for strings to values that we will use

as a symbol table so that variables can be looked up at runtime. The

?-> syntax indicates that the return type is a context function. An

earlier blog discusses that, but in short, it allows us to thread our

Env symbol table through the computation easily.

Here is the main body of the code.

def eval[A : Numeric](exp: Exp[A]): WithEnv[A] = exp match case Var(id) => handleVar(id) case Val(value) => Right(value) case Add(l,r) => handleAdd(l,r) case Sub(l,r) => handleSub(l,r) case Div(l,r) => handleDiv(l,r) case Mul(l,r) => handleMul(l,r) def handleAdd[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WithEnv[A] = eval(l) + eval(r) def handleSub[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WithEnv[A] = eval(l) - eval(r) def handleMul[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WithEnv[A] = eval(l) * eval(r) def handleDiv[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WithEnv[A] = eval(l) / eval(r) def handleVar[A](s: String): WithEnv[A] = summonEnv.get(s) match { case Some(value) => Right(value) case None => Left(EvalError.SymbolNotFound) }

Those arithmetic operators you see are operating not on integers,

doubles or some other concrete type, but are working on a type A that

has a Numeric instance. You may wonder then how that + operator

knows what to do? The answer is that I implemented an instance of

Numeric for the type Numeric[Either[EvalError,A]].

// Implement Numeric for EvalResult given evalResultNumeric[A: Numeric]: Numeric[Either[EvalError, A]] with { def add(fa: EvalResult[A], fb: EvalResult[A]): EvalResult[A] = { fa.map2(fb)((a,b) => a + b) } // ... and so on }

Whilst this is a lot of overhead for a simple program, as your programs scale in complexity, this level of abstraction lets you control effects as well as swap them in and out as your requirements change without having to rewrite the core logic.

As an example, let's introduce a Monad Transformer and show how to integrate it with the program above.

WriterT

Let's say we want to take an existing effectful program and add a new effect to it. The effect I will demonstrate is logging. There is a data type called Writer which represents a value and a log.

Writer[W,A](run: (W,A))

This is not very interesting on its own but if you make a program from

Writers, sequencing them together using the Monad's flatMap operation

for example, then the end result consists of a final value and a log

for each step of the program.

But since I already committed to using Either, if I change the type to

Writer then I would lose the ability to handle errors. Instead what I

want is to keep the Either effect and wrap it with the capability of

the Writer monad.

Monad transformers are the answer. Now the trouble with monads is that they don't compose manually together. As I covered in a previous blog, applicatives do. You can take any two applicative effects such as Either and List and compose them with simple functions.

With Monads the composition of any particular monad has to be hand-crafted, so if I want to stack a Reader on top of an Either, which I do, then I need to implement a ReaderT (reader transformer).

It only needs to be implemented once and for all and can then be applied to any other Monad (not just for Either). The idea is to make an implementation of Reader that wraps another Monadic data type.

case class WriterT[F[_],W,A](private val wrapped: F[(W,A)])

Here you can see the definition of the WriterT data type. The difference between WriterT and Writer is that the WriterT wraps an existing monad. Note that there is no need to constrain the higher-kinded type F to be a Monad, but later on when we use it in various ways it is possible to constrain F to be a Functor, Applicative or Monad depending on the use-case. Choosing the type bounds that constrain what the wrapped type must support based on the individual functions needs gives you more flexibility.

For example, if you have a data type that has a map operation but no meaningful way to make a flatMap, you can still use the Monad transformer as long as you only use Functor level methods.

Lifting

To use WriterT there needs to be a mechanism to take your inner data type (Either in this case) and make an instance of WriterT. That can be done like this in my implementation by using the WriterT constructor. For example let's say we have an Either instance we can transform it to a WriterT like this.

val e1: Either[EvalError,Int] = Right(10) val w1 = WriterT(e1.map(n => (List.empty[String], n)))

It's not straightforward because the WriterT wrapped type must be

F[(W,A)] and we had an F[A]. That is why I need to use the map

operation to take any value the Either may have and combine it with an

empty log. Here we assume the log is a list of strings and Scala is

able to infer that too.

Since this needed often the lift method is often added which takes care of creating an empty log message and mapping it for us.

object WriterT: def lift[F[_],W, A](fa: F[A])(using m: Monoid[W], F: Functor[F]): WriterT[F,W,A] = WriterT(F.map(fa)(a => (m.zero, a))) // ... val e1: Either[EvalError,Int] = Right(10) val w1: WriterT[[A] =>> Either[EvalError,A],List[String],Int] = WriterT.lift(e1)

Couple of interesting things to note about the lift method type signature. For one you can see that the log must be a Monoid. A Monoid is a type that must have two useful operations that make it useful for logs: It must be able to produce an empty element of whatever type it is specialized for, and it must be able to join that type together.

This gives the user the flexibility to use any data type for the log and not have to worry about providing an empty log or an append function. The example here is a monoid since it is a list of strings. Obviously we can produce an empty list, and the append function is also trivial, so if you look at my Monoid instance for lists you can see the implementation is trivial.

Another interesting thing is the Functor type constraint. As I mentioned above, although we call them Monad transformers, they can be used with Functors, Applicatives and Monads. Since the lift function only needs map, it needs only the Functor type constraint.

Evaluating expressions with a log

Now I'll walk through the changes needed to convert the expression evaluator from having the return type Either, to being one of WriterT[Either]

// Without log type WithEnv[A] = Env[A] ?=> Either[EvalError, A] // With log type WithEnv[A] = Env[A] ?=> WriterT[[A1] =>> Either[EvalError, A1], List[String], A]

The next step is to make small changes to my programs implementation to manage this new type. As you can see, the simplest change, handling a basic numeric value, just involves lifting our original Either and adding a log entry.

1: def eval[A : Numeric](exp: Exp[A]): WithEnv[A] = 2: exp match 3: case Var(id) => handleVar(id) 4: case Val(value) => WriterT.lift[[A1] =>> EvalResult[A1], List[String], A](Right(value)).tell(List(s"Val $value")) 5: case Add(l,r) => handleAdd(l,r) 6: case Sub(l,r) => handleSub(l,r) 7: case Div(l,r) => handleDiv(l,r) 8: case Mul(l,r) => handleMul(l,r)

You can see in line 4 the code is a matter of lifting the value wrapped in an Either. The type annotation is needed and creates some noise. I use the tell function to add a log entry for this step.

tell is a method on the WriterT data type itself, and it takes

advantage of the log types monoid to combine this new log entry with

any prior ones.

def tell(l1: W)(using m: Monoid[W], f: Functor[F]): WriterT[F,W,A] = WriterT(wrapped.map{ (l2,a) => (m.combine(l2, l1), a) })

By this technique at the end of a computation we should see a log of entries.

For example, the expression Val(10) would be logged as "Val

10". Having a step-by-step log of your application has various uses

including the following.

- Debugging. View the state of your computation in detail

- Auditing and statistics. Analyze the log of your computation for business information.

- Restore a failed computation. You can log at each step enough information to resume an expensive computation that may have been interrupted.

These kinds of benefits come with traditional logging, but building it into your application in a pure and type rich way can amplify the benefits.

Let's take a look at the symbol table lookup part of the program.

def handleVar[A](s: String): WithEnv[A] = summonEnv.get(s) match { case Some(value) => { WriterT.lift[[A1] =>> Either[EvalError,A1],List[String],A](Right(value)).tell(List(s"Var $s ($value)")) } case None => WriterT.lift(Left(EvalError.SymbolNotFound)) }

Again the change is virtually mechanical. We lifted our old code and

added the tell call to add some logging information. When we view

variable lookups in the log you will see something like Var("x")

written as Var x (7) where 7 is its value in the symbol table.

Extending numeric

def handleAdd[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WithEnv[A] = eval(l) + eval(r)

The remainder of the program involves expressions like this one. We

use the + operator to add two other expressions together. How that

works is a combination of operator overloading, extension methods and

implementing an implicit implementation of Numeric for our new WriterT

return type.

Here I'm defining an implicit instance of Numeric that handles things are Writers around Eithers. In previous posts, this is where I first implemented addition for different types of number, and then added the ability to handle errors in a type safe and functional manner.

I'm just extending that technique to handle a more complicated type.

given evalResultWNumeric[A: Numeric]: Numeric[WriterT[[A1] =>> Either[EvalError, A1], List[String], A]] with // ... implementations

The implementation of Add assuming a Monadic instance is available is as follows.

val M = writerTMonad[[A1] =>> Either[EvalError,A1], List[String]] def add(fa: EvalResultW[A], fb: EvalResultW[A]): EvalResultW[A] = { M.flatMap(fa) { a => M.map(fb){ b => a + b } } : EvalResultW[A] }

Which does the job but it doesn't include any logging. We can add that too.

def add(fa: EvalResultW[A], fb: EvalResultW[A]): EvalResultW[A] = { M.flatMap(fa) { a => M.flatMap(fb){ b => val result = a + b val w1: EvalResultW[A] = WriterT.lift(Right(result)) w1.tell(List(s"Added $a and $b giving $result")) } } }

Note that by nesting the flatMaps we have access to a,b and the result

of the computation so we can put all of that into the tell call,

resulting in a log like Added 22 and 23 giving 45.

There's nothing really wrong with this implementation, but it's

important to always think about the principle of least power. Did I

really need a Monad here? Well in fact there is a great function for

applying a computation across two different effects and that is

map2. It also requires only Applicative, so I can use that instead.

val App = writerTApplicative[[A1] =>> Either[EvalError,A1], List[String]] def add(fa: EvalResultW[A], fb: EvalResultW[A]): EvalResultW[A] = { App.map2(fa)(fb) { case (a,b) => a + b } }

This simplifies the code greatly but notice that I am no longer logging anything. Unfortunately, I no longer have access to the result of the computation. One clean solution I found here was to write a helper method that is like a logging version of map2. Like map2 it takes a function of two arguments to map the effect values, but it takes a second function that takes the two values and their result and lets you build a log entry from them.

def mapTell2[A,B,C,F[_],W](fa: WriterT[F,W,A],fb: WriterT[F,W,B],fabc: (A,B) => C,fabcw: (A,B,C) => W) (using m: Monoid[W], f: Monad[F]): WriterT[F,W,C] = { val r = fa.unwrap().map2(fb.unwrap()){ case ((al,a),(bl,b)) => val c = fabc(a,b) val w = fabcw(a,b,c) val prev = m.combine(al,bl) (m.combine(prev,w),c) } WriterT(r) }

While this looks like a handful what it is really doing is straightforward. Like map2 the input is two effects. First I unwrap them which gives us the inner effect, and running map2 on those gives the log and the value of each effect.

Once I've run the user function fabc on those values, I have the result value c and I can use that to build a log with the fabcw function. Finally, we need to combine the prior logs with the new log and return the result.

Here's the function in action.

def sub(a: EvalResultW[A], b: EvalResultW[A]): EvalResultW[A] = { mapTell2(a,b,(a, b) => a / b,(a,b,c) => List(s"$c: subtracted $a from $b")) }

By moving all that complexity into a helper function, each operator is now quite simple.

[info] running Scala3EvalEitherTWriter WriterT(Right((List(Var y (6), Var x (7), Val 10, Var z (22)),45))) Var y (6) Var x (7) Val 10 Var z (22) exp01 WriterT(Left(DivisionByZero))

In summary, you can use WriterT to convert any effectful program into one with step-by-step logging.

ReaderT

Another useful data type with a Monad instance is the Reader. As the name may imply, this is the conceptual opposite of Writer. i.e., instead of a computation writing its progress to a log, the Reader provides an environment of some type that the application can read from as it progresses.

In the program so far I've been using Scala 3 context functions to pass around the symbol table. There are reasons you may want to do that with a Reader instead. Perhaps you want to take advantage of the compositionality and lawfulness of Reader. Perhaps you want the context function reserved for some other purpose. Of course you may be using Scala 2 and not have access to the context function feature at all.

In one of my videos, I show the process of replacing context functions with the ReaderT monad transformer. Let's walk through the process here.

First of all let's look at the data type. Like the WriterT, the ReaderT wraps another higher kinded type F. As you can see, there is a second type parameter R, which is the type of the read-only environment. Also, you can see from the signature is that what the ReaderT contains is a function from R to the F[A]. How that is used will become clear.

case class ReaderT[F[_],R,A](run: R => F[A])

Just like with WriterT we also would benefit from a lift function that

lets us take any instance of F and wrap it. Here I'm saying if you

have some effect F[A] I will give you a ReaderT that wraps it. You

can run it with some environment and it will yield that F[A] again.

object ReaderT: def lift[F[_],R,A](fa: F[A]): ReaderT[F,R,A] = ReaderT(_ => fa)

When rewriting the program above we can now look up variables from the symbol table. We are returning a function that when given an environment can search it for the required symbol.

def handleVar[A](s: String): RResult[A] = ReaderT((env: Env[A]) => env.get(s) match { case Some(value) => Right(value) case None => Left(EvalError.SymbolNotFound) })

Literal values are also simple, just lift the Either from before.

case Val(value) => ReaderT.lift(Right(value))

The arithmetic operations don't change at all since ReaderT has an applicative instance we can just go ahead and use map2.

def add(fa: EvalResult[A], fb: EvalResult[A]): EvalResult[A] = { fa.map2(fb)((a,b) => a + b) }

Here is what needs to be done to run the code. The main difference is that we build a chain of Reader effects then execute them by passing an environment to the run method.

val env1: Env[Int] = Map("x" -> 1, "y" -> 10, "z" -> 100) val exp1 = Add(Mul(Val(10), Var("y")),Var("z")) println(eval(exp1).run(env1)) // Right(100))

WriterT and ReaderT

One thing I find wonderful about functional programming is its compositionality. I've shown that you can stack WriterT and ReaderT on top of any effect to imbue that effect with more capabilities.

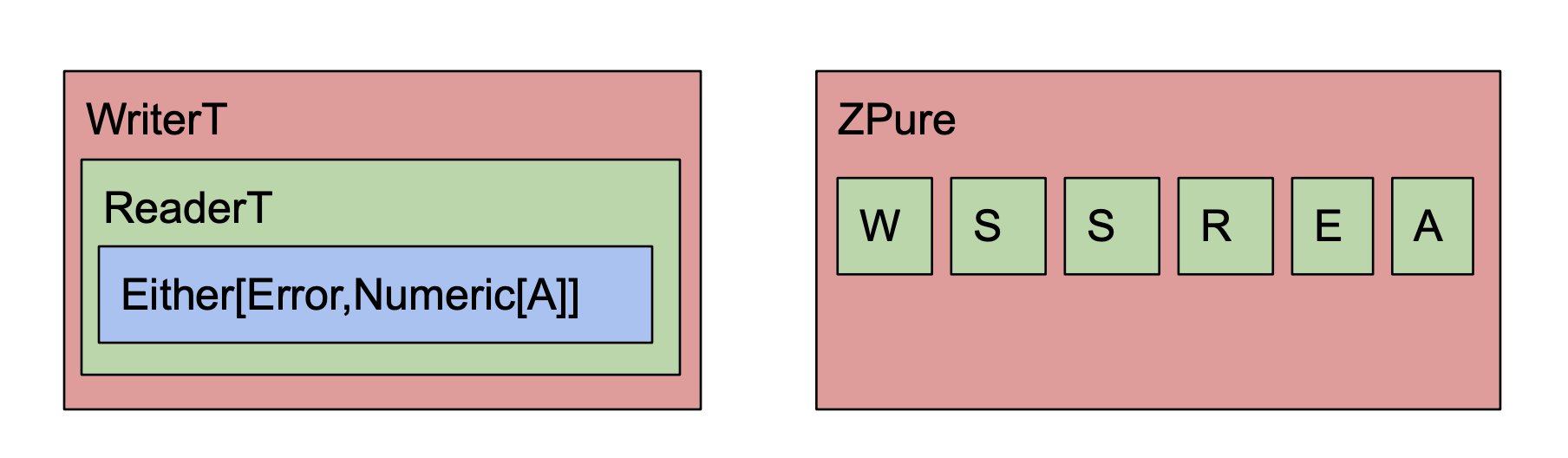

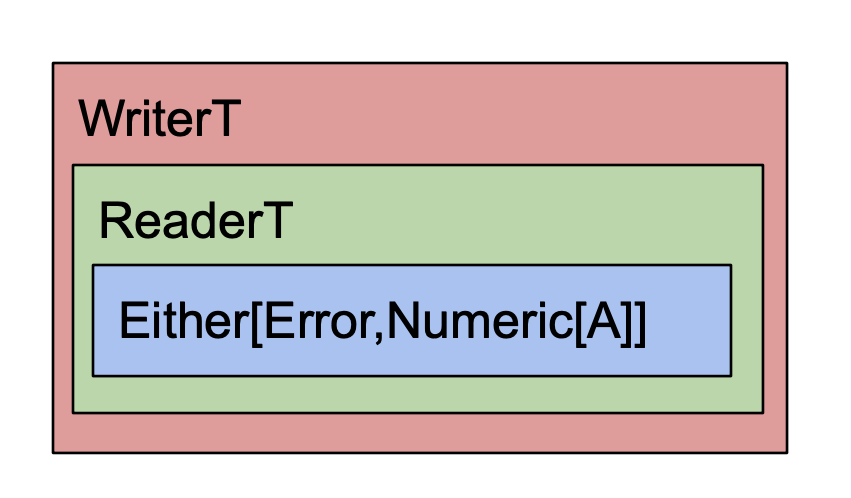

Now given that WriterT can wrap a monadic effect to give that effect logging, and further that ReaderT itself is a monad, it follows that you can wrap WriterT around ReaderT to give some effect the powers of both! This would work the other way around, and of course, you could also make an EitherT monad transformer, giving even more possibilities.

The next step is to change the programs return type to be…

WriterT[ [RA] =>> ReaderT[[EA] =>> Either[EvalError, EA], Env[A],RA], List[String], A]

Next to modify the program to handle the new effect types.

The implementation to get a value is easy enough. Starting from the inside out the value is put into an Either, lifted into ReaderT and lifted once more into WriterT.

case Val(value) => WriterT.lift( ReaderT.lift( Right(value))).tell(List(s"Literal value $value"))

Handling variable lookup we take care of the lookup first then wrap that into a writer.

def handleVar[A](s: String): WriterT[[RA] =>> ReaderT[[EA] =>> Either[EvalError, EA], Env[A],RA],List[String],A] = WriterT(ReaderT((env: Env[A]) => env.get(s) match { case Some(value) => Right(List(s"Looked up var $s ($value)"),value) case None => Left(EvalError.SymbolNotFound) }))

I'll skip the rest of the program since the theme is the same; wrap the reader code with the writer code and you're done. Let's take a look at how to run the program.

val envMap: Env[Int] = Map("x" -> 7, "y" -> 6, "z" -> 22) val eval1 = eval(exp1).unwrap().run(envMap) eval1.foreach { (log, value) => println(s"Result is $value\n") log.foreach { println(_) } }

Here you can see that our program has to be run sort of inside

out. eval(exp1) gives us a WriterT. By calling unwrwap I get the

ReaderT inside it, which I can then run by passing the environment.

The response is either an error or a tuple of our log and result, which we can then iterate over to print it out.

Result is 990 Looked up var z (22) Literal value 10 Literal value 2 Divided 10 by 2 (5) Literal value 2 Subtracted 2 from 5 (3) Looked up var x (7) Looked up var y (6) Multiplied 7 by 6 (42) Added 3 to 42 (45) Multiplied 22 by 45 (990)

Monad Transformers - some takeaways

You can see that monad transformers offer some expressive power since they allow us to manually combine different effect types to get the benefit of them all at once.

This comes at significant cost though. All this nesting creates additional JVM objects that take up heap space and may cause extra work for the garbage collector.

For the programmer, the ergonomics are not great. You have to remember the level of nesting you're at at each point of your program and make sure to do the right amount of lifting.

Just look at this single simple expression. So much space is taken up by the type signature, all the simplicity and elegance is lost.

def handleAdd[A : Numeric](l: Exp[A] , r: Exp[A] ): WriterT[[RA] =>> ReaderT[[EA] =>> Either[EvalError, EA], Env[A],RA], List[String], A] = eval(l) + eval(r)

Now there ways to help out the Scala compiler and reduce the amount of boilerplate, namely "kinda curried type parameters" which is a technique used heavily in Scalaz and Zio.

https://tpolecat.github.io/2015/07/30/infer.html

Thinking that the poor type inference is maybe my fault I've also written this code using Scalaz and Cats and you can see that each implementation has its pros and cons. (BTW in these libraries ReaderT is called Kleisli)

Reader Writer example in Scalaz

Reader Writer example in Typelevel Cats

Both implementations had the same problem as I did when not writing out the types in full. Scalaz had the same trouble inferring that my type was applicative so I had to summon the instance explicitly.

implicit val rwApply = Apply[WriterT[List[String],Kleisli[Either[Error,?],Env[A],?],?]] rwApply.apply2(x,y) { case (a,b) => a + b }

Cats was able to handle it resulting in less code and needed less type annotations in general.

x.map2(y) {

case (a,b) => a + b

}

Effect rotation with Zio Prelude's ZPure

Zio Prelude is a new library that acts as a sort of add on library to ZIO (a zero-dependency Scala library for asynchronous and concurrent programming) which provides an alternative approach to functional abstractions in Scala.

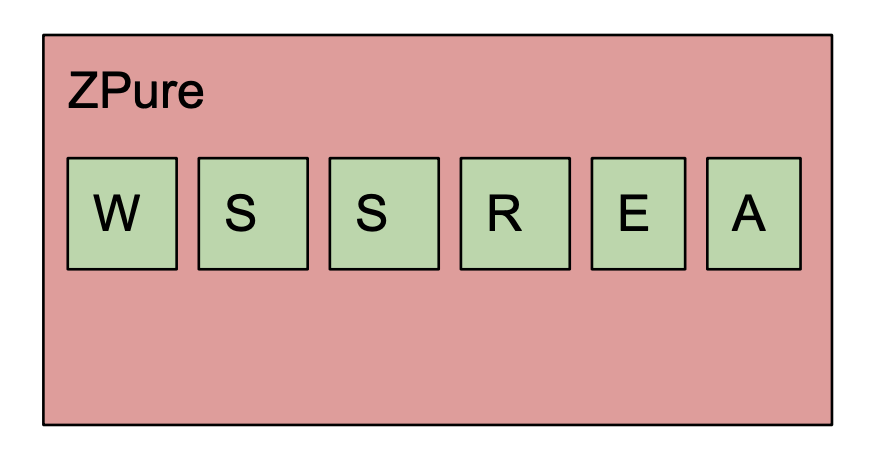

For the purposes of this blog I'm interested in particular

experimental data type within the library called ZPure. ZPure has 6

type parameters and supports the operations of monads, applicatives

and functors, albeit the names are changed and some of the

abstractions too.

From Prelude's own source code "ZPure can be used to model a variety

of effects including context, state, failure, and logging.", let's see

how it compares to monad transformers to implement the program above.

ZPure has six type parameters, which may seem like a lot, but bear in mind that every time you combine monads you get more type parameters, but they are stacked vertically not horizontally. With ZPure you start with all the different effect types one might need but you don't need to keep adding more and more, and you don't suffer from creating multiple objects per layer of effect.

In the diagram the parameters are.

WLogging. The type of logs that this effect produces, analogous to WriterSState. There are two S's because the type encodes an input and output state typeRReader. The type of the read-only environmentEError. The type of the error channelAValue. The type of the happy path computed value

Just as before all I need to do is change my programs effect type and modify the implementation accordingly. The code for this section can be found here.

Although Prelude supports Scala 3 now I rewrote my program in Scala 2 in order to do the Scalaz and Cats versions, so the following is also pre Scala 3 friendly code. First I made a sealed trait to represent the error types and an alias to indicate that my log will be strings.

Note that ZPure is opinionated about the logging type. In the more

conventional approach, the log has to be a monoid instance. With ZPure

the log is handled using the ZIO Chunk data type which is a

high-performance data structure with a pure functional interface. What

that means for us is that we can consider our log type as a single

entity and not worry about how it is appended.

sealed trait Error object SymbolNotFound extends Error object DivisionByZero extends Error type Log = String

These types will represent the E or error, and W or log. We can

encode our symbol table using the R parameter.

type Env[A] = Map[String, A]

The final type looks like this.

type Result[A] = ZPure[Log, Any, Any, Env[A], Error, A]

Note that I am not using the initial or updated state here so I use Any for those parameters so as not to constrain them.

Once again let's start with the implementation of literal values.

case Val(value) => ZPure.succeed(value).log(s"Literal value $value")

What's going on here is simple and refreshingly free of type annotation. Firstly I construct a ZPure consisting of the literal value, and then add a log using ZPure's log method.

Now let's implement the symbol table lookup of variables.

1: def handleVar[A: Numeric](s: String): Result[A] = { 2: ZPure.environment[Any, Env[A]].flatMap { 3: env => 4: ZPure.fromOption(env.get(s)). 5: mapError(_ => EvalZPure.SymbolNotFound). 6: flatMap{ 7: a => 8: ZPure.log(s"Var $s value $a").as(a) 9: } 10: } 11: }

First I use the ZPure.environment to summon the symbol table and

flatMap over it so we can access it as a concrete value env.

Remember that looking up the variable in the symbol table is going to return an Option since it is a normal map get. We can then use the ZPure.fromOption to convert that to a ZPure.

We may be a ZPure at that point but we have the wrong error type. In ZPure and option is simulated by yielding a success value A for Some, or giving Unit in the error channel to indicate None. This reuse of the error channel is neat, but since I would like a homogenous error type for the program I need to convert that error channel from unit to my own custom Error type.

To do that I use mapError which takes a function to map the error from one type to another.

The final step is to add a log. Since I would like the log to show

both the variable name and the actual value I have to nest it inside a

flatMap so we can access the success value. The last thing to note

here is the as which helps the type system make a ZPure of the right

type.

implicit def numericZResult[A: Numeric]: Numeric[Result[A]] = new Numeric[Result[A]] { def add(x: Result[A], y: Result[A]): Result[A] = { x.zip(y).flatMap{case (a,b) => ZPure.succeed(a + b).log(s"Add $a and $b")} } // and so on

The final component is to make an instance of Numeric. Prelude takes

the approach to naming that concepts should be plain English where

possible, so it uses succeed instead of pure or unit and

similarly zip instead of applicative terminology.

That being the case, we use zip here to combine the left and right side effects and apply the appropriate arithmetic operator.

So far so good, but we can't log the result of the computation. This is easily solved.

def add(x: Result[A], y: Result[A]): Result[A] = { x.zip(y).flatMap{case (a,b) => { val result = a + b ZPure.succeed(result).log(s"Add $a and $b ($result)")} } }

The last part to note is the driver code to run the program.

val eval1 = eval(exp1).provide(env1).runAll() eval1._2 match { case Right(value) => println(s"Succeeded with value ${value._2}") eval1._1.foreach { l => println(l) } case Left(err) => println(s"oops! $err") }

Here I run eval to create the effect, provide to give it the runtime environment and runAll. To be clear what eval does is not run a program, but build a data structure of objects based on the ZPure operations, and that data structure is evaluated in Prelude using an efficient interpreter, that yields the result of the program, the log and any state changes.

Succeeded with value 200 Literal value 10 Var x value 1 Mul 10 with 1 (10) Var y value 10 Mul 10 with 10 (100) Var z value 100 Add 100 and 100 (200)

Conclusion

In this post I implemented and motivated ReaderT and WriterT and transforming monads to combine effects. Even in Haskell where they originated, monad transformers come with caveats about performance and ergonomics. In Scala they are not used often.

There are techniques and libraries to make their use more convenient. Although I have not used it Cats MTL offers solutions to some of the problems, but it is not widely used.

Although ZIO Prelude's ZPure is still somewhat experimental it seems offer the benefits of monad transformers such as composability and a prinicipled type safe api. But, it is also much easier to work with and anecdotally more performant on the JVM.

In the future I'm looking forward to exploring some traditional functional programming problems using Prelude and ZPure.

Hope you enjoyed this post and got to the end. You can find my contact details at the top of the page; I always welcome feedback and questions.

(C)2021 Justin Heyes-Jones, All Rights Reserved.