Monads in Scala 3 for the Genius

Introduction

This is a companion blog the seventh Functional Justin YouTube video which you can find here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1FSxbmZpCE

The source code shown in the video and in the fragments below can be found here: https://github.com/justinhj/evalexample/blob/video-7-r3/src/main/scala/livevideos/Video7.scala

The goal here is to make 10-15 minute videos that each cover an isolated topic in pure functional programming with Scala. There is an also overarching goal to cover a certain number of base topics you need in functional programming. Once that is complete I will start doing deep dives into FP libraries such as Cats and Zio.

Monads for the Genius

The title may sound like clickbait, and it most surely is, but the point is that for most Scala programmers, even those working with functional programming libraries, most of what you need to know about Monads is what the type signatures of the methods are and how you can leverage those in your code. For bonus points you can learn the Monad laws and implement your own lawful Monad instances.

If you want to know why Monad consists of pure (or unit) and flatMap, and why Monads are functors (they have map) you need to dig a little deeper, and for that reason I targeted this post at the genius, but perhaps the curious would be a better way to put it, it hopefully will not be a really difficult topic to follow.

In this post and the accompanying video I will show the category theory you need to understand monad and derive an implementation of the monad type class from that theoretical foundation. From there the next step is to show the monad in use on effects and how to implement and use flatMap (or bind).

Just enough Category Theory

Category theory is a candidate for a theory that describes all of mathematics, and has been applied to a number of areas.1. If you want to know more about it than the very basics then I recommend Category Theory for Progammers.2

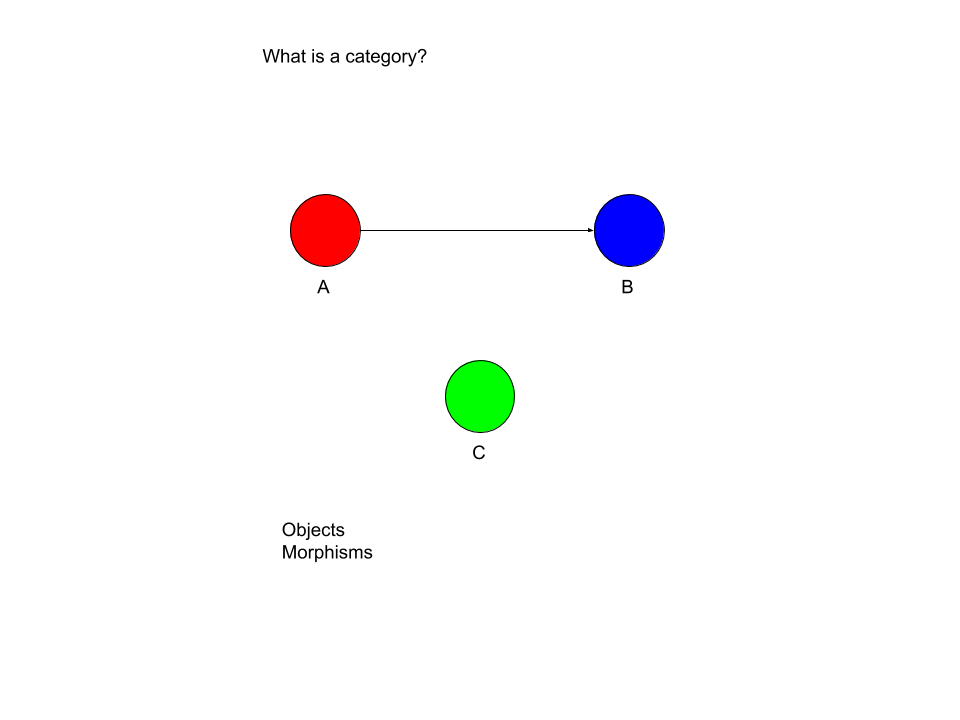

The essence of category theory is the category itself, which consists of objects and morphisms that transition from one object to another.

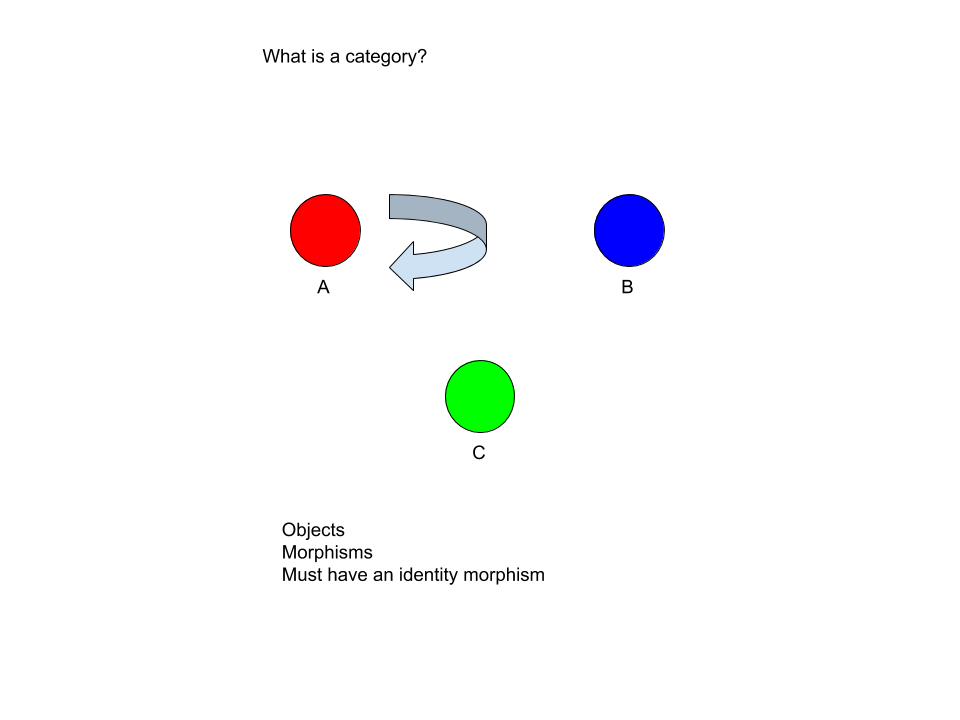

In addition there must be an identity morphism on each object. This simply gives you a way to transition from an object to itself.

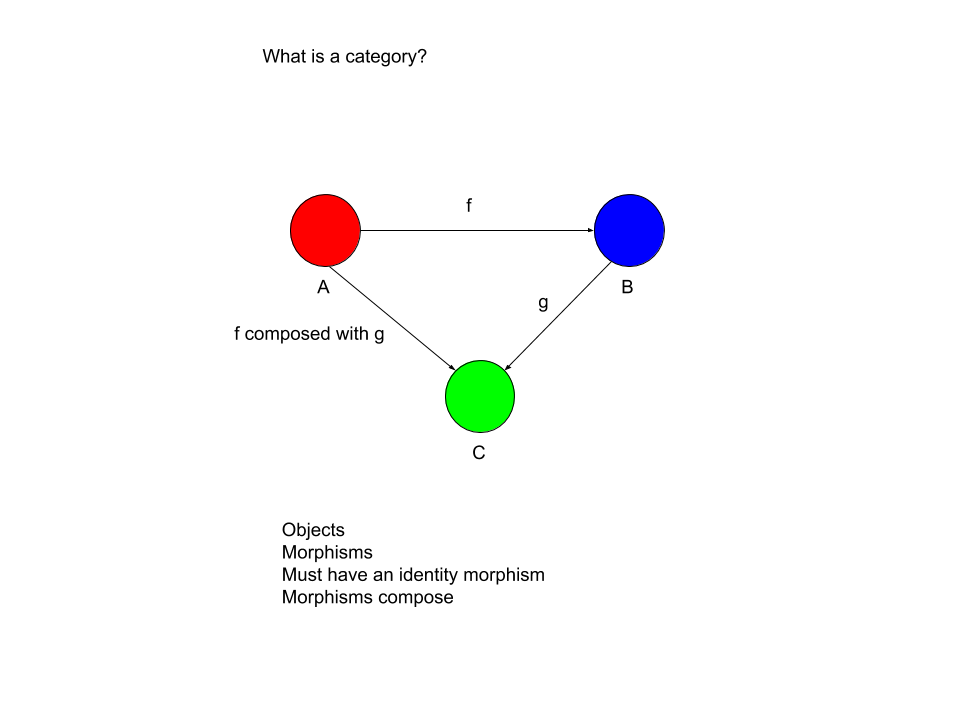

Morphisms between objects can compose. Here we have a morphism from A to B (f) and another from B to C (g). We can compose f and g, giving us a single morphism from A to C.

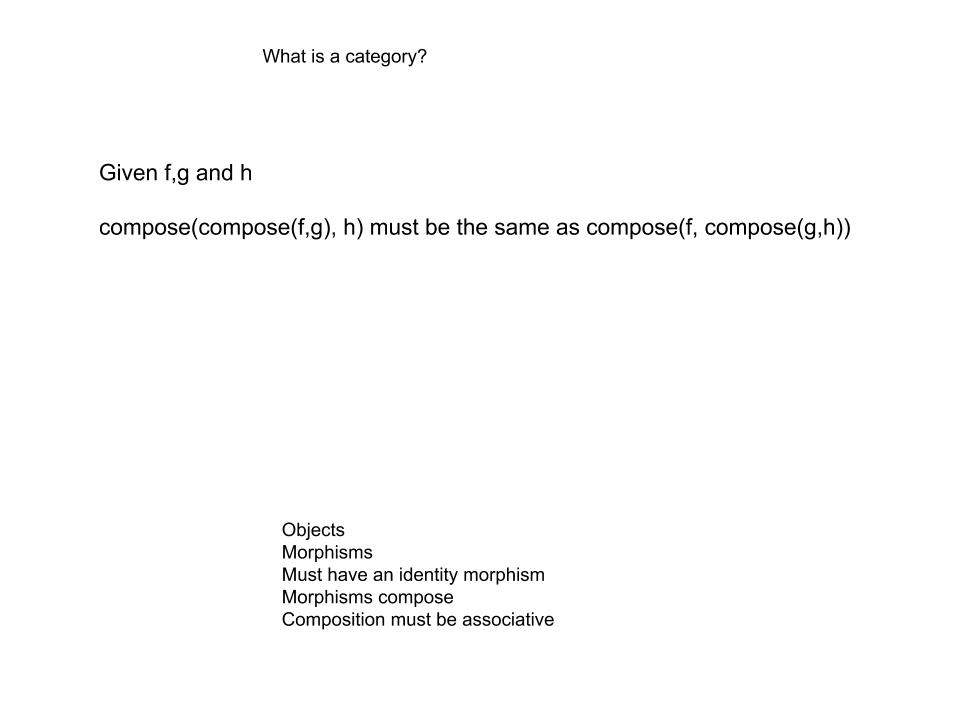

Composition must follow the associative law. As shown below that means if we have three morphisms f,g and h, it doesn't matter how we compose them as long we don't change the order they are applied. We can compose them in two different ways.

The category of Scala types and functions

Let's make the concept of a category more concrete by seeing how it can be encoded in Scala. One example of a category is the category of Scala types and functions.

In the code below we have a lawful category. The objects are the Scala types (Ints, Booleans, Strings) and the morphisms that take us from one object to the next are ordinary Scala functions. There are three examples f,g and h.

Remember to be a category we need an identity morphism, which turns out to be simply the Scala identity. (A => A).

The other thing we need is a way to combine morphisms that must be associative. We have that with the built in function compose!

As you can see in the code it is straightforward to show the laws of the category are upheld.

// Category of Scala functions val f: Int => Int = a => a + 1 val g: Int => Boolean = b => if(b == 1) true else false val h: Boolean => String = c => if(c == true) "Winner!" else "Loser!" // Identity f.compose((a: Int) => identity(a))(0) == f(0) f(0) == f.compose((a: Int) => identity(a))(0) // Composition must be associative h.compose(g.compose(f))(0) == (h.compose(g.compose(f)))(0)

Above you can see composing the identity function with f gives the same result as calling f alone.

You can also see that composition is associative. We compose h with g and f in different ways, without changing the order, and get the same results.

A monad is just a functor in the category of Kleisli arrows

What's the problem?

Well there are two problems here. For one many readers may be saying "What? Surely a monad is a just a monoid in the category of endofunctors!"3

Perhaps another group are completely lost. Well the famous quote about monads is absolutely right, but that is a different way to arrive at Monads than the simpler one we are looking at here.

Instead we will arrive at Monads by making a simple change to the

Category of Scala types and functions. The only change we will make is

instead of Scala functions of the form A => B we will instead use

what is known as a Kliesli arrow, which has the form "A => F[B].

You may recognize that shape of function from the argument to Scala's flatMap. In other words it is the type of function that maps a pure value to an effectful value.

Let's look at how we can encode this new category directly in Scala as a monad!

Note I will call the Monad type class Monad1 to avoid confusion with the more usual Monad definition in the code.

trait Monad1[F[_]]: def unit[A](a:A): F[A] def compose[A,B,C](lf: A => F[B], rf: B => F[C]): A => F[C]

In the definition above we have all we need to implement the category of Scala objects and Kliesli arrows (and incidentally this is, by definition, a monad).

Firstly what are the objects? Just like before the objects are Scala types.

Next what are the morphisms? We stated the morphisms would be of the form A => F[B].

Finally what is the identity? The identity has the same form as any

other morphism except that it maps a type to itself, so the identity

is A => F[A]. We can implement that in Scala with the unit

function above.

With Scala functions we used the compose function. Here we need to write our own code that composes two Kleisli arrows returning a new one. This is the direct analog of the compose function that works with simple functions.

For convenience, just like with any other Scala 3 type class we need a way to summon a Monad of a particular type into existence and for that we write the apply function as follows.

object Monad1: def apply[F[_]](using m: Monad1[F]) = m

Implementation of Monad for Option

given optionMonad1: Monad1[Option] with def unit[A](a:A) = Option(a) def compose[A,B,C](lf: A => Option[B], rf: B => Option[C]): A => Option[C] = { a => lf(a) match { case Some(b) => rf(b) match { case Some(b) => rf(b) case None => None } case None => None } }

You can see that unit is just a call to the Option constructor, whilst

compose will return a new function that first applies lf to the

input, then if that yields a value and not a None, it will apply rf

to that yielding a new Option. Please note I made an overly complex

version of this in the video, and only realized once it was too late.

Now we can write code that composes "effect generating" functions (or Kliesli arrows) together. Here I make three simple functions that operate on Scala values and produce Options.

Here we use the Monad1 option to compose f,g and h…

def f(n:Int): Option[Int] = if n == 4 then None else Option(n) def g(n:Int): Option[Boolean] = if n%2==1 then Option(true) else Option(false) def h(b:Boolean): Option[String] = if b then Some("Winner!") else None val fcomposed = Monad1[Option].compose(f,g) val fghComposed = Monad1[Option].compose(fcomposed, h) def i(a: Float) = 0.0 println(fghComposed(1)) println(fghComposed(2)) println(fghComposed(3)) println(fghComposed(4)) // Output: // Some(Winner!) // None // Some(Winner!) // None

The Monad laws

At this point we've shown that one implementation of a Monad involves the unit and compose functions. We can now see a demonstration of the monad laws in this form.

Left and right indentity laws are shown by composing a function with unit. This is equivalent to what we did with Scala functions.

// left and right identity m1.compose(f, m1.unit)(1) == f(1) f(1) == m1.compose(f, m1.unit)(1)

We can also demonstrate the associtive law in action, whereby composing f,g and h works both ways.

m1.compose(m1.compose(f,g), h)(1) == m1.compose(f, m1.compose(g,h))(1)

What about flatMap?

So far so good, we conjured up a monad from just category theory and a simple twist on the category of types and functions. You may be wondering how we get from this new definition of Monad to the one we see in Cats and Scalaz, and why even in the Scala standard library we have flatMap but not compose for Kliesli arrows.

Well fortunately flatMap can be written in terms of compose, so we can be assured that the more convenient and familiar representation of Monads is exactly equivalent!

def flatMap[F[_],A,B](fa:F[A])(f: A => F[B])(using m: Monad1[F]): F[B] = { // F[A] => F[A] // A => F[B] m.compose((a: F[A]) => identity(a), a => f(a))(fa) }

I found this implementation a bit tricky to understand at first but if

you look at it and reference the Option instance above it should make

sense after a little thought. The "trick" is that we are given an

F[A] and so we pass that as the first argument to compose using the

identity function to get it back unchanged. (Mapping an F[A] to itself

is actually the map function of Functor!)

compose from flatMap

Should your starting point be the more traditional Monad with pure and flatMap, you can in fact derive the compose function as follows.

import org.justinhj.typeclasses.monad.{given,_} def compose[F[_],A,B,C](lf: A => F[B], rf: B => F[C])(using m: Monad[F]): A => F[C] = a => lf(a).flatMap(rf)

Final remarks

One last thing you may be interested in is that you can implement monad as pure and flatmap, pure and compose or as third set pure, map and flatten.

My favourite reference for exploring Monads in Scala is the so called red book which devotes chapter 11 to the subject.4 The nice thing about that particular book is it encourages the sort of exploration and discovery of these concepts that makes them so fun to work with!

There is some duplication in the names when we use category theory in Scala that can cause confusion. Here's a little guide.

| Purpose | Functions | Kleislis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | identity | unit | pure | return | point |

| Sequence two effects | n/a | flatMap | bind | ||

| Flatten a nested effect | n/a | flatten | join |

Finally it was really my goal here to show that there is not much to categories and therefore not much to monads. The terminology is unfamiliar but I think the concepts are quite straightforward. I would love to know if this blog and/or video failed to make sense, so feel free to reach out to be on the youtube comments or via the contact details above and I will take on board your suggestions.

Footnotes:

Uses of Category Theory https://math.stackexchange.com/a/1210742/2914

Category Theory for Programmers https://github.com/hmemcpy/milewski-ctfp-pdf

James Iry and the famous monad quote https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3870088/a-monad-is-just-a-monoid-in-the-category-of-endofunctors-whats-the-problem#3870310

Functional Programming in Scala https://www.manning.com/books/functional-programming-in-scala