Monoids for Production

What’s in this post?

- Why use category theory in Scala?

- Quick intro to Semigroups and Monoids

- How to implement Monoids in Scala

- Using the Cats and/or Scalaz libraries to work with Monoids

- An example of Monoids in production code

- Testing the Monoid laws of your Monoid instances

- Bonus footnotes: Mini reviews of some Functional Programming in Scala books

The code for this post can be found here:

Category Theory and Scala

If you’ve already read a few Monoid tutorials, you may want to skip to Monoids in Production.

Lifting abstract algebraic structures like Semigroup and Monoid from mathematics can make simple concepts sound complicated. While it would be tempting to come up with new words that sound more familiar, it pays for us to adopt these terms because they let us talk precisely about the things in terms of their operations and laws. It is useful for us to have a shared vocabulary with which we can communicate to other programmers and our compilers, what our types can, and cannot, do.

To read more on pure functional programming in Scala some great books are: Functional Programming in Scala 1, Functional Programming for Mortals2 and Advanced Scala with Cats 3.

Semigroups

A semigroup is an algebra that has a binary associative operation; a function that takes two values of the same type and combines them into a single value.

Integer addition, for example, forms a semigroup:

def plus(a: Int, b: Int) : Int = a + b

plus(plus(1,2),3)

//res1: Int = 6

plus(1,plus(2,3))

// res2: Int = 6

Note that as long as we don’t change the order in which the additions are performed, we get the same result. It is this property, associativity, that makes addition with integers a semigroup. Multiplication works the same way:

def multiply(a: Int, b: Int) : Int = a * b

multiply(multiply(1,2),3)

//res1: Int = 6

multiply(1,multiply(2,3))

// res2: Int = 6

Another example that follows the Semigroup pattern is joining strings together. Take the following strings:

"Hello" "," "World" "!"

As long as we don’t rearrange the strings, we can append them in any order we like and get the same final result. Imagine 4 strings a,b,c and d:

a b c d

ab cd

abcd

a b c d

ab c d

abc d

abcd

a b c d

a b cd

a bcd

abcd

We can do the actual operation in any order and get the same result, which is captured by the property:

op(op(x,y), z) == op(x, op(y,z))

This property is useful because we know that we can do optimisations. If we have long lists of integers we can divide them into smaller ones, run the appends in parallel, and then combine the results. We can use a left fold or a right fold without worrying about the order of operations.

Foldable[List].foldLeft(List(1,2,3), 0){_ |+| _}

//res1: Int = 6

Foldable[List].foldRight(List(1,2,3), 0){_ |+| _}

//res2: Int = 6

Note that to fold a list we need the list, a binary operation to combine each element, and a “zero” value. Without a zero value, it’s impossible to combine all the elements of the list into an accumulator. For example, if we have a list with a single item, the first step of the foldLeft would be:

Foldable[List].foldLeft(List(1), ???){_ |+| _}

??? |+| 1

If we had a zero value available for the type our semigroup is defined for, we could run a fold using that zero value instead of passing it ourselves. The syntax would then be simply:

Foldable[List].fold(List(1,2,3))

//res1: Int = 6

By adding a way to get a zero for a type, we turn a semigroup into a monoid.

Monoids

Although it’s called zero, it is not always the number zero. Zero is some value that can be combined with other values without changing the original value. Here are some examples:

Integer addition - the zero value is actually 0

3 + 0 == 3

0 + 3 == 3

Integer multiplication - the zero value is now 1

3 * 1 == 3

1 * 3 == 3

Logication or - the zero value is true

true || true == true

false || true == true

String append - the zero value is the empty string “”

"Justin" ++ "" = "Justin"

Monoids in Scala

In Scala, we can implement Monoids as a Scala type class, a way to extend the behaviour of existing types. We will encode its operations as a trait. Note that this is an abstract definition. We will then define instances of Monoids that make concrete versions of the operations.

trait SemiGroup[A] {

def op(a: A, b: A) : A

}

trait Monoid[A] extends SemiGroup[A] {

def zero : A

}

And a sample instance implementation:

val intMultiply = new Monoid[Int] {

def zero = 1

def op(a: Int, b: Int) : Int = (a * b)

}

intMultiply.op(10,20)

// res1: Int = 200

intMultiply.op(10,intMultiply.zero)

//res2: Int = 10

In our production code, we’ll use the Scalaz and Cats Monoid implementations instead of rolling our own. This gives us premade instances for many common types, syntactic sugar to make working with Monoids more concise, a bunch of useful combinators that we can use like fold and even automated law tests that verify our own instances obey the laws.

Let’s have a look at Scalaz for example:

import scalaz._, Scalaz._

val l1 = 10 |+| 20 |+| 30

//res1: Int = 60

Foldable[List].fold(List(10,20,30))

//res2: Int = 60

In the example we first use the Monoid combine function using the syntax helper |+| and in the second we use the Scalaz foldable instance for list to do the same job. There is a Monoid instance defined for integer that implements addition, so that is used.

We could also define multiplication (or any other associative operation) and use that instead. For example, Scalaz has a Tag feature which lets us change the datatype of a thing at compile time only, and it can then pick up a different monoid implementation. Tags.Multiplication is a tag for numbers that has a Monoid instance that multiplies:

l1.foldMap{a => Tags.Multiplication(a)}

// res3: Int @@ Tags.Multiplication = 6000

Note that we use foldMap instead of fold here because we need to map a function over the list to add the multiplication tag. We could also just put a locally scoped implicit monoid for multiplication, but that would break type class coherence. See FP for Mortals for more on Tags and type class coherence. In Cats there is no Tags mechanism so you must find other ways to get your alternate implementations in scope.

Finally one more example from my sample code MaxMonoid.scala, a Monoid instance for the maximum of two numbers:

import scalaz.Foldable

import scalaz.Monoid

import scalaz.std.list._

import scalaz.syntax.semigroup._

implicit val maxIntMonoid : Monoid[Int] = Monoid.instance[Int]({case (a : Int,b : Int) => Math.max(a,b)} , Int.MinValue)

val testAppend = 10 |+| 20

// res1: 20

Scalaz provides a function instance that takes two arguments; the combine operation and the zero value for a type, so we can easily define a new Monoid instance. Note that we can’t import all of scalaz._ like we did before because we don’t want to bring in the instance for Monoid[Int]. Once defined we can then use the fold over a list to find the max:

val l1 = List[Int](1,2,3,4,5,4,3,2,1,-10,1,2,3)

Foldable[List].fold(l1)

// res1: 5

Take a look at this post by Adam Warksi at Software Mill for more examples of Monoids and what you can do with fold:

https://softwaremill.com/beautiful-folds-in-scala/

Monoids in Production

You already know how to append strings and add numbers, why bother with all this fancy abstraction? Well, first of all we saw above how having a Monoid implementation enables us to use a wider range of combinators like folds and traversals; our intentions are made clearer with less code. When it comes to our application business objects, that may have more complicated append methods and be nested in multiple data structures, we can see that the expressive power of Monoids is a great advantage over an imperative solution. Let’s take a look at a real example.

Taking Inventory

- Image from Madlands - a former online iOS and Android game

In many MMOG (massively multiplayer online games) you manage a city that contains plots of farmland that produce food, oil and so on. On the backend we need to store the things that the player owns in a database. When in memory we represent the inventory as a map, where the keys are the types of resources we own, and the values are the quantity.

For example we represent the players’ resources using integer ids:

- Oil

- Gold

- Corn

A player with just some gold would have an inventory like this:

import cats._

import cats.data._

import cats.implicits._

val inventory = Map(2 -> 1000)

Imagine that the player buys 1000 Oil and 1000 Corn and this will cost 200 gold. We could write some code that iterates over the players’ inventory map and updates the new values, create new keys as necessary for items the player didn’t have. But fortunately because there is a Monoid instance for Map, we can simply combine the player inventory map with the purchases and costs map to get the new inventory:

val updatedInventory = inventory.combine(Map(1 -> 1000)).combine(Map(3 -> 1000)).combine(Map(2 -> -200))

//res2: Map(1 -> 20, 2 -> 600, 3 -> 20)

In this example we reduced the gold by 200 and granted the player 1000 of two types of resources. In fact we could simplify to just adding two maps together:

val updatedInventory = inventory |+| Map(1 -> 1000, 3 -> 1000, 2 -> -200)

//res3: updatedInventory: Map[Int, Int] = Map(1 -> 1000, 3 -> 1000, 2 -> 800)

The implementation of Map for Monoid gathers togethers the values with the same key and appends them with Monoid, meaning anything with a Monoid can be combined.

Map(1 -> "Hello") |+| Map(1 -> " ") |+| Map(1 -> "World")

//res1: Map(1 -> "Hello World")

We can also fold it like this:

Foldable[List].fold(List(Map(1 -> "Hello"),Map(1 -> " "),Map(1 -> "World")))

//res1: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "Hello World")

Produced Items

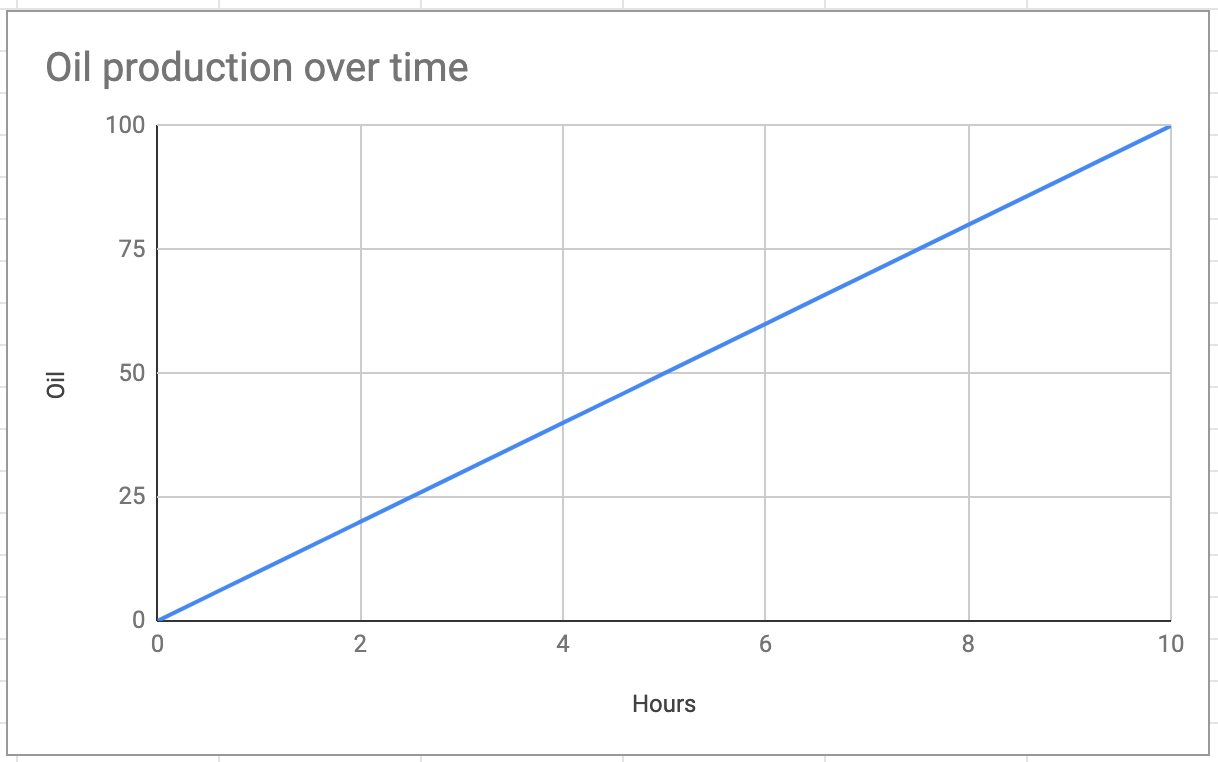

We stored the players inventory as a Map, and we can easily use Monoids to perform operations on inventories as well as lists of items and currencies. But also in our game the players had resources that increased or decreased over time. For example if you have a Level 1 Oil drill it produces oil at 10 units an hour. Over 10 hours it would accumulate 100 units of oil.

What we don’t want to do is have to constantly update the players production item count at some discrete interval. For one, that would be very costly on our servers, and for another we may want to show the resources increasing or decreasing in real time on the client.

In order to model this we can simply store the starting amount (this will be zero for a new oil drill), and the players rate of production. We also store the time the production began (when the oil drill is built).

With these three variables we can always calculate the current amount of the resource by the simple formula:

current_amount = initial_amount + (time_passed * production_rate)

Storing production items in this way means we can calculate the current value at any time to display it. Note that we can adjust the initial amount whenever we want by a positive or negative amount, and things will work out. But if we change the production rate then we need to update a few things. Firstly we calculate a new initial amount (the current amount from the calculation above). Then we store the current time, and adjust the production rate to the new one.

Whilst this is all straightforward, it complicates the adding and removing of items from the players inventory. We want to be able to remove 200 gold and add some resources just as we did before, and ideally we shouldn’t have to worry about things like what time it is and production rates.

Of course the solution is to model this by creating a Monoid instance for produced items, and that is what we did. There are two implementations and two demo programs to show the Scalaz and Cats implementations which have minor differences and caveats.

case class ProducedItem(snapshotAmount: Long, snapshotTime: Long, amountPerHour: Double) {

def currentAmount(implicit clock: Clock) =

snapshotAmount + (((clock.currentTimeMillis - snapshotTime) / Clock.oneHourMillis) * amountPerHour).toLong

}

Here you can see the amount and time of the last snapshot as well as the production rate amountPerHour. The player’s current amount is no longer a static field, but a function that calculates the current amount based on the snapshot data. Note that we are passing in a Clock object implicitly. We’ll see why later but for now you just need to know that a clock is a datatype that lets us get the time so we can make the calculation.

implicit def monoidProducedItemOps(implicit clock : Clock) = new Monoid[ProducedItem] {

def empty = ProducedItem(0, 0, 0)

def combine(p1: ProducedItem, p2: ProducedItem) : ProducedItem = {

val p1A = p1.currentAmount

val p2A = p2.currentAmount

ProducedItem(p1A + p2A, clock.currentTimeMillis, Math.max(Math.abs(p1.amountPerHour), Math.abs(p2.amountPerHour)))

}

}

Next we implement the Monoid instance for our new data type. The zero function is simply a ProducedItem with a snapshot at time zero, zero amount of stuff and zero production rate. While the combine (or append for scalaz) function is a bit more involved. It must calculate the current amount of both ProducedItems. The new snapshot value will be the sum of those p1A + p1A. The new time snapshot will be right now, which we get from the clock, and the new production rate is simply the production rate with the most magnitude.

Just to explain that a little; in our use case production items always have the same production rate for the same player. Whenever the production rate changes for an item, we update all items of that type. So typically we will always have the same value on each side of a produced item type. However the zero value has no way to know the production rate, so simply taking the biggest one does what we need. You need to pay attention to details like this on your own Monoid instances to make sure the combine operation makes sense with respect to your business logic.

Now we have all we need to start adding ProducedItems (there are example programs in the source code, or you can do the following at the Scala console to try it out).

import cats.syntax.monoid._

import cats.instances.map._

import org.justinhj.production._

import org.justinhj.production.productioncats.ProducedItem

import org.justinhj.production.productioncats.ProducedItem._

implicit val clock = FixedClock(System.currentTimeMillis + Clock.oneHourMillis)

val now = clock.currentTimeMillis

val inventory1 = Map(

1 -> ProducedItem(10, now - Clock.oneHourMillis, 10),

2 -> ProducedItem(10, now - Clock.oneHourMillis, 5))

val inventory2 = Map(

1 -> ProducedItem(-5, 0, 0),

2 -> ProducedItem(-5, 0, 0),

3 -> ProducedItem(1, 0, 0))

val inventory3 = Map(

3 -> ProducedItem(1, 0, 0))

val addInventories = inventory1 |+| inventory2 |+| inventory3

// addInventories: Map[Int, ProducedItem] = Map(

// 1 -> ProducedItem(15L, 1560220015450L, 10.0),

// 2 -> ProducedItem(10L, 1560220015450L, 5.0),

// 3 -> ProducedItem(2L, 1560220015450L, 0.0)

Now we can easily combine our ProducedItem structures, and of course we now use other combinators like fold:

import cats.Foldable

import cats.instances.list._

val listOfInventories = Foldable[List].fold(List(inventory1, inventory2, inventory3))

// listOfInventories: Map[Int, ProducedItem] = Map(

// 2 -> ProducedItem(10L, 1560220015450L, 5.0),

// 1 -> ProducedItem(15L, 1560220015450L, 10.0),

// 3 -> ProducedItem(2L, 1560220015450L, 0.0)

// )

The test of time

As promised we return to the Clock data type. This is implemented in production.Clock.scala and provides the following simple function to get the time:

trait Clock {

def currentTimeMillis : Long

}

There are two implementations; firstly there is a SystemClock, so called because it returns the system time. This one will be used in production so that your players corn grows correctly. The second is FixedClock which always returns the same time. This is to make testing easier. We want to be able to start our corn growing then check if it grew the right amount an hour later, and of course we don’t want the tests to run in real time. To get around this if you check my test classes such as org.justinhj.production.ProducedItemTestCats you can see that I that I make a fixed time clock with the current time and then set my test items to have a snapshot time of one hour ago. Having strict control over time like this is vital to testing time and date related logic in a principled way.

implicit val clock = FixedClock(System.currentTimeMillis)

val now = clock.currentTimeMillis

val pi = ProducedItem(10, now - Clock.oneHourMillis, 10)

Checking Monoids are lawful

The beauty of functional programming is we can build up solid foundations like this, and then go ahead and compose more complex programs from our simple lawful data types. But one caveat, did we implement a lawful Monoid? In order to make sure, I have include tests in both Scalaz and Cats style to show you how to use each library’s law checking facilities.

In this example we will use Cats. Instructions for this are here https://typelevel.org/cats/typeclasses/lawtesting.html but you can also follow my working example in the code.

class ProducedItemLawTestsCats extends CatsSuite {

implicit val clock = FixedClock(System.currentTimeMillis + Clock.oneHourMillis)

checkAll("ProducedItem.MonoidLaws", MonoidTests[ProducedItem].monoid)

}

With the correct imports and library dependencies you can now access MonoidTests[ProducedItem].monoid which will contain tests for each of the Monoid laws. It will in addition use Scalacheck to generate many random instances of your classes to give thorough empirical testing of whether the laws hold. Of course this check will not guarantee that your laws hold but it will certainly help you feel confident. Ultimately Scala leaves it as an exercise to the programmer to ensure that the laws are valid and automated testing is no substitute for your own reasoning. Note that in order to generate the tests we need an Eq instance for our data type which allows them to be tested for equality. We can automatically generate one that just compares each field of the class:

implicit val eqProducedItem : Eq[ProducedItem] = Eq.fromUniversalEquals

Now we can run our test suite and bask in the glory of our own brilliance…

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.left identity *** FAILED ***

[info] GeneratorDrivenPropertyCheckFailedException was thrown during property evaluation.

[info] (Discipline.scala:14)

[info] Falsified after 0 successful property evaluations.

[info] Location: (Discipline.scala:14)

[info] Occurred when passed generated values (

[info] arg0 = ProducedItem(4960954082650183831,1,1.5706606739076523E-208)

[info] )

[info] Label of failing property:

[info] Expected: ProducedItem(4960954082650183831,1,1.5706606739076523E-208)

[info] Received: ProducedItem(4960954082650183831,1560221194037,1.5706606739076523E-208)

Oh, no! What happened? It seems our laws do not hold, for left and right identity and other things besides. After a little thought it becomes clear, when we combine a ProducedItem with the zero value it should not change the original item.

val now = 1560221355576L

val oneHourAgo = 1560217755576L

ProducedItem(10, oneHourAgo, 10) |+| Monoid[ProducedItem].empty

// ProducedItem = ProducedItem(20L, 1560221355576L, 10.0)

Clearly, we can see that this is not correct. When we combined the two items we took a new snapshot and the time changed to now! So we changed the equality from true to false and broke the identity laws. At the beginning of this exercise we came up with a data structure that helps us represent items that increase or decrease over time, and in doing so we introduced these new variables. On the other hand from a business logic point of view, two produced items are the same if (and only if) their current amounts are the same. We don’t care about production rate or snapshot time or event current snapshot value.

Let’s rewrite our equals check to take this insight into account:

implicit def eqProducedItem(implicit clock : Clock) = new Eq[ProducedItem] {

def eqv(x: ProducedItem, y: ProducedItem): Boolean = {

x.currentAmount == y.currentAmount

}

}

And rerunning the tests we can see the tests are now all green!

[info] ProducedItemLawTestsCats:

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.associative

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.collect0

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.combine all

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.combineAllOption

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.is id

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.left identity

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.repeat0

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.repeat1

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.repeat2

[info] - ProducedItem.MonoidLaws.monoid.right identity

Check the Scalaz tests to see very similar code in action.

The End

This has been a small sample of how Monoids can help simplify your code, and make it more composable. Thank you for reading this post, please let me know via the links at the top if you have any questions or comments!

For more reading on Monoids check the books below. I also highly recommend this conference talk by Markus Haulck that shows some nice composition tricks Monoids When Everything Fits: The Beauty of Composition - Markus Hauck

Footnotes

-

Functional Programming in Scala (the Red Book) by Runar Bjarnsen and Paul Chiusano covers functional programming from first principles as you build your own implementations of immutable lists and options, before showing how to develop useful libraries in a pure functional style. Examples include a json parser and concurrency library. Next we are guided through all of the most common type classes like Functor, Monad, Applicative… what are their laws, what operations can be implemented. Finally we are shown how to control side effects using the IO Monad and the book ends with a sophisticated streaming IO implementation. Manning Publications now have a “livebook” version of the book where you can complete the (essential) exercises directly on the web page as you read. ↩

-

Functional Programming for Mortals by Sam Haliday is a practical and principiled guide to building systems with Scala using Scalaz. A real world example application is developed throughout the book, which also functions as a manual to Scalaz, demonstrating each type class in some realistic scenario. It will also appeal to Star Wars fans as Sam helpfully tells us what symbols like

|+|,<+>and@@represent both in Scalaz and in the Star Wars universe. Whilst aimed at mortals it will require some experience in Scala to hit the ground running. ↩ -

Advanced Scala for Cats by Noel Walsh and Dave Gurnell is a lighter book than the other two but covers the common type classes clearly and concisely. Rather than covering one big example application, small but realistic examples are given for the various features. Obviously from the title this focuses on the Cats library. Like the red book, this also contains exercises, althought they are not as rigorous or as difficult. This book accompanies Underscores training course. ↩